Selling the New Edge

This is an expanded, written monologue of the Apotheosis podcast episode. Podcast music by Nullsleep.

If you're first exposure to Mondo 2000's narrative of the Internet was with The Cyberpunk Handbook you might have looked no further—sending it to the trash heap—not even fit for recycling. But those who grew up and explored the Internet during Mondo's days didn't live in reverse like we're doing with this look back at cyber history. The handbook was the final push of California cyberpunk satire, but Mondo did live on the edge for a few years, much like the earlier zine version of Boing Boing.

This "edge" culminated in the publication of the essay/anthology/thought experiment named Mondo 2000: A User's Guide to the New Edge. For those just looking back at the history of Internet culture, if you wanted to get a handle on what Mondo was all about, this tome (although short) is much more appropriate than The Cyberpunk Handbook.

Before we begin, I want to point out that quite a few people had positive things to say about our previous look at Mondo, and shared similar feelings towards The Cyberpunk Handbook and the general lack of serious takes on the cyberpunk culture by Mondo writers. Codepunk co-host Bill Ahern had this to say:

Just finished reading the Cyberpunk Fakebook article. Loved it. Really timely too, because after I found my copy and started flipping through, I certainly went through the same emotions. In some sense, I always regretted that R U Sirius, who obviously never saw any need for gravitas in any form, became the face (for a while) of all things cyber. I get the need to not take oneself too seriously, but to never take anything seriously is equally as useless.

Bill pointed out that he started hunting down old issues of FringeWare Review, feeling that the zine was more what would happen if Mondo covered cyberspace seriously. Interestingly enough, FringeWare Review was founded by Jon Lebkowsky and Paco Nathan, both of whom also wrote, edited, and contributed to Boing Boing and/or Mondo 2000. We already established previously the crossover between Boing Boing and Mondo writers. Between FringeWare, Boing Boing, Mondo, and early Wired Magazine, it's worth mentioning the lack of diversity in opinions and writers. Most of these early zines and magazines shuffled the same handful of people around, and those people influenced the majority of early Internet and computer culture.

Reading the back matter of Mondo 2000: A User's Guide to the New Edge should very clearly tell you what you're in for. Outside of the Newsweek blurb, the very first sentence states:

Mondo 2000 will introduce you to your tomorrow—and show you how to buy it today!

Sadly, this isn't the first reference to "buying stuff" on the back matter. Another shared theme with Boing Boing. The rest of the back matter is typical hyperbole and carnival barking with references to smart drugs, digital outlaws, teledildonics (recall that The Cyberpunk Handbook had multiple references to bestiality—so no, you weren't going to escape the 12-year-old humor), and of course, media pranking… because much like Boing Boing, these "pioneers" of early Internet culture did it all for the LULZ.

I know I'm being hyper-critical in retrospect—and certainly did not complain this much during the initial Mondo run—but in hindsight, the messenger should be more than a satirical caricature of early adopters.

Much like the vastly satirical The Cyberpunk Handbook, Mondo's Edge is essentially organized as listicles and dictionary entries with quotes from various Mondo 2000 articles and contributors on one side and supporting text on the right. Honestly, this was an ingenious setup for several of the entries as it often gave historical context for either the subject matter being quoted or the person who wrote and/or gathered the information. It also included icons to inform the reader of items that could be found and purchased in Mondo's online shop. Such a tactic might be what colors my response to some of Mondo's later publications—specifically their attempt at collected works. Both books were published towards the end of Mondo 2000's publishing run, and as the publication came to a close, the quality of work seemed to rely on pranking, remixing, and satire with a "buy now" link thrown in for good measure. Is it a book meant to inform? Or is it a catalog meant to sell their warez? I think the previously mentioned first sentence on the back matter tells us exactly which of the two it is.

I promise we'll venture more into the content of Mondo's Edge, but I wanted to start with a critical evaluation of where it sits in the zeitgeist and culture of Internet prominence. Much like The Cyberpunk Handbook, Edge is forgettable and mostly represents an aggregation of articles, definitions, and ideas from the magazine consolidated into an encyclopedia and published as an attempt to make some last minute cash on the Mondo name. It doesn't hold as much crass satire as the Handbook, which is good, but does little to establish itself as a torch-bearer of the "edge" ideas it promises to reveal.

The fact that Boing Boing's Happy Mutant Handbook and both Mondo books were published around the same time (mid-90's) shouldn't be lost on anyone, and this is also roughly the same time when the Dot-com bubble began to accelerate and much of the computer and Internet subculture was being rewritten, dressed in a suit, and pushed into the mainstream. With the mainstream taking over many of these ideas and being better at writing stories on them than either Boing Boing or Mondo, it left the organizers of the subculture scrambling for a differentiator. Unfortunately, for those on the left-libertarian side of the equation pushing open source software, hacking, and experimenting with Internet culture, Bill is right that for a long time, R U Sirius was unfortunately the poster child, which made it all the easier to dismiss those in the cyberpunk movement—and those in the left-libertarian free software camp—while embracing the new tech capitalism on the horizon.

Before I get too deep into trashing Mondo's Edge, I want to be clear that I'm not trashing the writers featured. My criticism is for the editorial direction of both Mondo and this book at this particular point in culture. There are gems to be found—or at least summaries and reprints of gems found elsewhere that have been migrated into the pages of this small encyclopedia.

Michael Synergy—in speaking of hackers and crackers—espouses a philosophy on the "freedom of information" mirrored by that of Aaron Swartz himself. Synergy points out that, to him, the most important president was Richard Nixon who removed the gold standard from money, resulting in "real" money being nothing more than ones and zeros in a computer ledger. Synergy's take has a whole new dimension with the advent of blockchain technologies and the token economy today.

Synergy's take on money is echoed by none other than Emmanual Goldstein, editor of 2600 Magazine, who points out that "The more digital the society gets, the more we'll be able to completely change money."

When it comes to Mondo's Edge note that Goldstein's comments are relevant, prescient, and deserve contemplation. But also note that Mondo's Edge includes these comments as a single paragraph in a chapter on "Crackers" and then moves on. The content has value, but the editorial and the book reduce that value, leaving us with little other than a link to the Mondo catalog to "buy more." But don't worry, there's an entire chapter on geek humor, taking up roughly 10 times the space as a small Goldstein quote. And for every Richard Stallman quote on hacker ethics, there is an equivalent analysis on hip-hop.

I like Digital Underground as much as the next guy, but considering the short length of the book, did so much of an "Internet culture" book need to be about mainstream music?

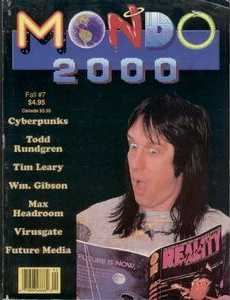

On page 14 of Mondo's Edge, just after the Rudy Rucker introduction, R U Sirius takes the wheel, but it only takes to page 15 to see an 8 1/2 x 11 full page photo of Sirius himself. What is a book about the new edge of culture without a full head-shot from its number 1 peddler? During its most popular Mondo was considered a bleeding edge representation of emerging culture in California and Sirius took on an almost cult-like persona (some of this was detailed by Douglas Rushkoff in Cyberia, and we'll get back to that in the future). Sirius made a desperate attempt to blend multiple cultural areas (emerging technology, fringe culture, underground music, pranking) to try to become the next MTV, but seemed to lack the discipline and skills of cohesion to pull it off for long. His last grasp was a handful of self-deprecating, prankster-heavy, content-light books to sell the image (and some products) and try to stay in the global consciousness a little longer.

Although Sirius' direction with Mondo led him to prominence, it also led the subculture to a divergence where those in technology could either continue to gravitate towards the merry pranksters of Mondo and Boing Boing or those wishing to make computer science a career or life-long passion could turn to the increasingly innovative and business-oriented Wired Magazine. The disappointment is that the failure of the "new edge" to present a detailed, fulfilling view of the future left many in the subculture with little alternative but to turn to a Wired Magazine that was absorbing and trampling on the counterculture, while spinning a new yarn for growth capitalism.

Wired itself remained a strong force in the subculture initially—even using some of the same editors and writers as Boing Boing and Mondo. But its serious tone made it more palatable to business analysts, venture capitalists, and unfortunately, the up-and-coming tech worker. Eventually Wired sold out to Conde Nast to become little more than paper to serve advertisements, but that's another story.