The Subversive 80's through the Lens of Max Headroom

No ads, no tracking, and no data collection. Enjoy this article? Buy us a ☕.

Modern culture siphons value from past generations in order to pre-package quantity for quick financial extraction. The result of this is the raiding of authenticity from past generations into a meme-ified version of itself. Much of the modern generation seems to live off of memes, YouTube video clips, and recycled collage advertisements that feign nostalgia. Those a part of this modern generation might recognize Max Headroom as a goofy head in a television box with an annoying stutter and bad fashion sense, but the reality is much darker, dystopian, and subversive—and it's a perfect reflection of the youth movement of the 80's coupled with the emerging niche literature of that time period.

As odds would have it, there is a small group of individuals circulating online that remember and revere the oddities and cultural experimentation of Max Headroom. Conversational artificial intelligence pioneer Ben Brown (creator of Botkit and current Microsoft employee) counts himself among this group. Artist and technologist Bill Ahern (Codepunk co-editor) is another. In fact, it was Ahern's interest in producing a Max Headroom episode for the Codepunk podcast that inspired and spawned several recent media pieces on the character and the character's relationship to culture.

Max Headroom himself (itself?) was a highly experimental creation that blended music, artificial intelligence, and cyberpunk, and the end result was much more subversive than most remember thanks to New Coke commercials perverting perceptions. The truth is that the original Max Headroom pilot was less than an hour of grainy made-for-TV goodness meant to launch Max as a video DJ for a UK music video show (you can find episodes on YouTube with a quick search).

In addition, there were Easter eggs littered throughout the TV movie that lent credence to Max's geek credentials (or at least showed you that the writers were true cultural insiders). For example, the network on the show is Network 23—a number with well-known counterculture and modern occult significance known as the 23 enigma. In particular the number 23 has great significance with the pseudo-religion Discordia, and plays an important role in the works of counterculture elite Robert Anton Wilson. Wilson himself acknowledges that his first exposure to the strangeness of 23 came from a conversation with author William S. Burroughs. This number has continued to carry significance into the modern era through Chaos Magick and genre writers like Grant Morrison (e.g., his Invisibles comic book series).

Another good example of solid geekery is the number of the apartment in the raid at the very beginning: 42. This is clearly a reference to Douglas Adams and his Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy where 42 is the answer to the meaning of life. 42 also has significance in the works of author Lewis Carroll and others.

Quality entertainment and red herrings aside: From the beginning, Max Headroom: 20 Minutes into the Future had its geek credentials in order, and gave us a glimpse of a dystopian future where people are treated as nothing more than data, media dominates the landscape, and society is manipulated for corporate gain: A traditional cyberpunk dystopia that resides a little too close to home.

Protagonist Edison Carter discovers that the massive media conglomerate that he's working for is using a new form of subliminal messaging to sell advertising that has resulted in fatal consequences. Carter—being chased through the building—attempts to escape a parking garage on a motorcycle, but hits his head as the villainous child genius of the company manipulates a platform lift. What does he hit his head on? A low clearance sign with the words "Max Headroom 2.3m." The company, however, doesn't want Carter to disappear, so the aforementioned boy genius constructs a virtual version to fool audiences. The experiment is a failure, and both Carter and his digital version are sent off to be disposed. Lucky for them, the goons disposing of them do the typical goon thing and try to sell them each for money. Digital Carter (constantly repeating "Max Headroom") is sold to a pirate television station, while organic Carter is sold for organ donation. Long story, short… Carter awakens, defeats the villains, and exposes the leadership at the company, which brings down a few individuals, but as with any true dystopia, the network itself remains every vigilant and intact.

Meanwhile, Digital Carter has been christened Max Headroom by the pirate radio station, whose proprietors work with him to slowly bring through some form of humanity. He's given his own show, and they ride off into the sunset, setting up Max's video DJ gig in the real world.

Despite the counterculture influence, 20 Minutes into the Future is still a television movie, and it was specifically designed to introduce and spin-off a video disc jockey. In the movie, Max Headroom eventually escapes into the data-stream with a couple of cyberpunk music heads running a pirate radio station: The implication being that even though the free love of the 70's hippie era left us short of truly being free, the cyberpunks now controlled cyberspace, and the new subversive music that 80's era parents hated would be shots of Jaeger for the soul of the cyberpunk youth.

Why a video disc jockey?

When MTV began it started with images of the Apollo moon landing—ideas of the future of humanity—playing to rock music. The first music video was Video Killed the Radio Star—humanity transitioning through technology. MTV drove sales of albums that weren't getting radio play, altering the landscape of music and culture. As rock music transitioned in the 80's, MTV was there. MTV allowed for the 80's pop/experimental to rise as a paradigm of futuristic philosophy, one-hit wonders, and commentary on the very consumerism the era was pushing. During the 90's, it was a place to find alternative music that wasn't widely popular in car radios. Would Nirvana and the grunge movement of teenage angst ever have been a thing without the video for Smells Like Teen Spirit?

MTV video disc jockeys (referred to as VJs) weren't television personalities like the latter day Carson Daly. Kurt Loder was a Rolling Stones journalist before joining the company. Kennedy went on to become a host of several Fox Broadcasting shows. Both Loder and Kennedy describe themselves as libertarian, but much more in the left-libertarian tradition of the original computer underground. Kennedy—a Nixon evangelist—leaned hard right, but eventually softened up her social conservatism, even officiating the gay wedding of friends. Kennedy's politics might be most famous for chanting "Nixon now" during an MTV event for the Clintons. But remember, this was during a time when young people were highly skeptical of government in general—regardless of political affiliation.

What about Tabitha Soren? At 19 years old she was in the Beastie Boys video about fighting against the oppression of your parents in order to live freely. She then embarked on an MTV career introducing teenagers and young adults to the importance of politics and voting—interviewing presidents, leaders, important political figures, and winning awards along the way.

Even the most commercialized personality at the time—Downtown Julie Brown‐had a sizable impact on culture as a mixed-race UK import who turned an on-air mistake into a catch-phrase. This is a company that launched Pauly Shore into the stratosphere by cultivating his surfer-bro party alter-ego during a time when America was transitioning out of the experimental 80's, forgetting it's Vietnam War sins, and was entering into economic recovery. Shore was also a performance comedian whose parents owned the Comedy Store where he opened for Sam Kinison. Not exactly "commercial"—although he clearly cultivated his image in that direction.

MTV in the 80's and early 90's was a pioneer of the counterculture, spinning audio-visual pleasures that put pictures to the subversive music you previously only heard on vinyl. Today, MTV is a pale shell of what once powered the collective, subversive mind-share of America's youth.

MTV was a microcosm of a larger cultural transition that played out as the 70's counterculture disintegrated, leaving the remnants to wrestling with empowerment through knowledge vs. empowerment through consumerism. In order to understand this, we have to take a look at the geopolitical shifts that have shaped the previous 30-40 years.

We can fundamentally trace the development of regional and national cultural shifts by arbitrarily looking at slices of decades. The 70's counterculture movement was active in anti-war protests, hallucinogenics, and communal activities, and encompassed most of what we consider a hippie generation. When we turned the corner to the 80's, consumerism was high on the list of societal rites of passage, while the counterculture morphed into an exploration of cyberculture as "machines of loving grace" captivated the counterculture pioneers. This was a new frontier connecting internal explorations with external components. The 90's meanwhile entrenched us in the consumer culture, as Reaganomics and consumer-driven economies took full control through an obsession with GDP. This saw the escalation of neoliberalism as well as the emergence of peripheral sub-genres. For the 2000's, I was at a loss for an appropriate title, but Joe Matheny helped me by labeling this the "blank generation"—a blank culture where sub-genres were mostly test audiences created for consumption by corporations for maximum financial extraction. This corporatism embraced a formulaic media approach—attempting to carbon copy and bottle even the slightest smell of a dollar bill.

Of course, various cultures indeed span across decades. Much like generations of people, these generational cultures are fluid throughout these time periods and not static within a specific decade. But the important consideration is the recognition of how progressive and expansive cultural explorations hit a brick wall of regressive thought that transformed most of what was great about counterculture movements into a maximization of financial extraction for corporate shareholders.

The 80's was the battleground.

Although the transition from counterculture into cyberculture upheld some of the left-libertarian ideology of the mystic 60’s and 70’s, the geopolitics of the 80’s ushered in a new focus on economy, consumption, and wealth. This impacted all walks of life in the 80’s, but it played out on the smaller stage as software developers began facing the dilemma of free software vs. commercial software—spurned on by Bill Gate’s founding of Microsoft and willingness to attack software sharing through legal means.

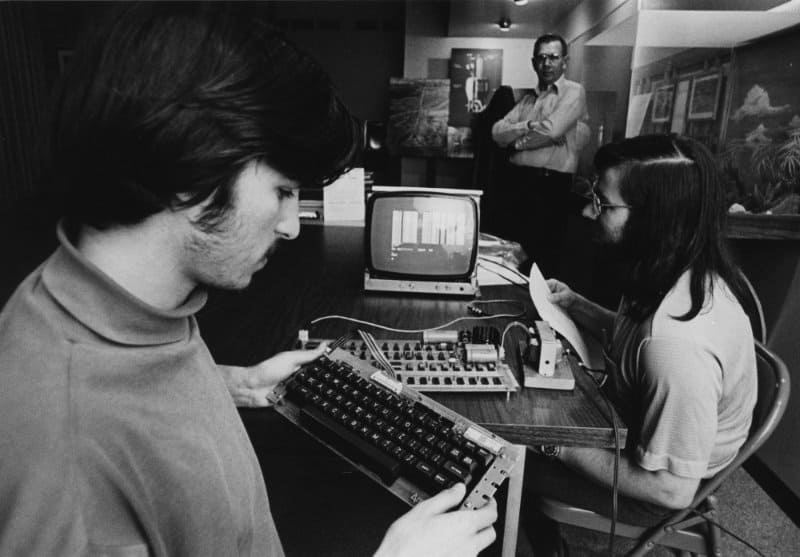

Many of the Southern California computer pioneers, hobbyists, and hackers held onto left-libertarian ideology. With the advocacy of Timothy Leary, we moved from psychedelic drugs to computers as the next level of experience. Stewart Brand took the Whole Earth Catalog online as The WELL. Exploring virtual systems and creating software was a form of collective societal empowerment. The computer was meant to set the individual free and open a new frontier of exploration and empowerment, but they were slowly becoming the minority as culture as a whole was moving towards consumerism and corporatism.

If Alan Moore’s Watchmen was a look into how the world would have been shaped with a continued influence from Richard Nixon, cyberpunk is an examination of what would happen if the conservative principles of the 80’s escalated to its natural conclusion.

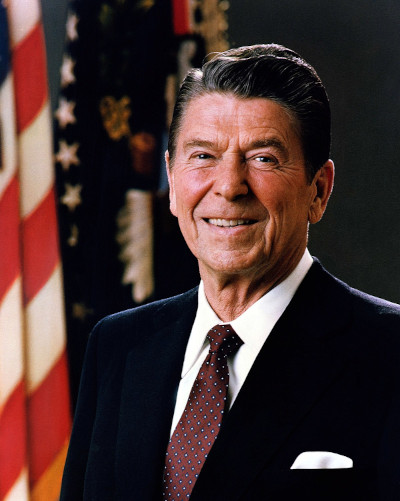

When Ronald Reagan was elected, he began championing supply-side economics, which became the platform for American conservatism, cutting taxes on the upper class, widening the gap between the rich and the poor, and ushering in the ability of corporations and shareholders to take advantage of a financially extractive economy. Despite the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts, Reagan was also a champion of deregulation, and his reduction in government spending deprived investment in the public sector, including research and university funding. Reagan’s "War on Drugs" deeply impacted impoverish minorities and is still felt to this day. Reagan’s foreign policy included interventions in the Middle East and a Cold War arms race that still resonates with the Doomsday Clock watchers of today.

Across the Atlantic, Margaret Thatcher was also busy deregulating industries, opposing trade union power, and privatizing state-owned institutions. Her support of the poll tax was regressive and disproportionately affected impoverished individuals. She also began flirting with nationalist ideology as her skepticism of any European coalition grew.

A shared opposition to communism drew Reagan and Thatcher together at a time when the promise of wealth and success through conservatism invigorated the Alex P. Keaton’s of the world, but the emergence of computers and the Internet helped to keep a subculture alive that was against conservative interventionism. Even though government spending might have decreased, funding for the military increased, and the Justice Department started to take an interest in online communities and so-called hackers. Cyberpunk literature and imaginings took supply-side worshiping and deregulation to its natural conclusion and gave birth to a world overwrought by corporations and consumerism.

America essentially lost its soul with the Vietnam War, and when the hippie movement failed, the children of the counterculture generation embraced the wealth and power expressed by the Reagan 80’s and Reaganomics. This generational split pitted Boomer parents against Generation X children, and launched an era of consumerism, catalyzed by supply-side economics that increased the wealth gap. Supply-side economics, a global economy through trade deals, and the emergence of credit as a defining factor transitioned America from a maker economy into a consumer economy, but also shifted ideology to be more conservative.

Family Ties is a good example of a television show that defined this generational gap: Pitting Alex P. Keaton and his Reagan worship against his hippie parents.

As liberal politicians worked to break the hold that Reagan had on the nation, they moved further to the right, embracing trade and corporatism, producing their own neoliberal agenda that was nearly indistinguishable from the Republican platform in terms of economic, financial, and business matters.

Those that didn’t fall into the Reagan trap, took their counterculture principles (or the principles of their parents) and embraced niche areas of cultural and political ideas. Younger Gen X’ers became lost in a soulless consumer economy, but some found escape through subcultures emerging throughout the nation, including cyberpunk.

Drew Austin has an excellent newsletter called The Kneeling Bus, and in one of his issues, he quotes Richard Meltzer on the notion that rock-and-roll had value until it was everywhere—this is the idea that scarcity breeds contemplation, which breeds catharsis. Radio made music readily available, but still on rotation. Want the song? Buy the album. As technology progressed and the tape deck emerged, you could record off the radio in lieu of buying the whole album. Nowadays, you can just buy songs individually, or stream them whenever you want. Artists who painstakingly crafted everything from the music, the song order, the album cover art, the lyric sheets, and the videos that expanded the message they wanted to convey have been replaced by immediate, single consumption. The crafted story is lost.

Largely this is the result of our financially extractive economy. Large corporations dominate the music (and overall entertainment) industry, looking to execute on the mythic algorithm to create the most viral pop song. The demand from shareholders is for financial growth, so corporations are looking to spend the least for the greatest return on investment. This is why the movie industry invests so heavily in sequels, and if not sequels, the movies follow a formulaic approach devoid of a soul. Music is no different, and all of the major music companies invest mostly in the formulaic pop music that rotates on the radio and YouTube. Originality is gone. Messaging is gone. The very emotional, cathartic, and transformative origins of music have been completely stripped out—eliminating the value of storytelling—leaving us with Billboard charts of clones that can be converted to data, measured, and duplicated for financial growth.

This is the very dystopian future that Max Headroom implied—people as data. The subversiveness of music and music videos was a taste of the youth versus corporate battle of the 80's, but that ultimately fell once corporations found a way to absorb and commercialize the salient talking points of the musical counterculture. Once finished, they turned their attention to other genres and niche areas—and their conquest, unfortunately, hasn't slowed.

What Max Headroom gave us, was truly a look at 20 minutes into the future: Our future.